Making the invisible visible – a pictorial tribute to Lennart Nilsson

Maximilian Ackermann1, 2, 3

Lennart Nilsson (1922–2017), a Swedish master photographer, revolutionised biomedical visualisation by merging artistic vision with scientific precision. His collaboration with the Karolinska Institute in the 1950s led to the first detailed images of human embryonic development, later published in Life magazine and in the book A Child is Born (1965). These works transformed humanity's understanding of the origins of life and established a new standard in scientific imaging. Building on Nilsson’s legacy, this pictorial tribute explores the principle of “form follows function” in biological systems, emphasising how structure reflects physiological purpose. Using advanced imaging techniques such as microvascular corrosion casting and hierarchical phase-contrast tomography (HiP-CT), we visualise organ architecture at cellular resolution. Current initiatives, including the Human Organ Atlas Hub and the HIMALAYA project, integrate imaging, molecular and clinical data to deepen our understanding of human anatomy and disease – continuing Nilsson’s vision of revealing life’s hidden structures through the fusion of art and science.

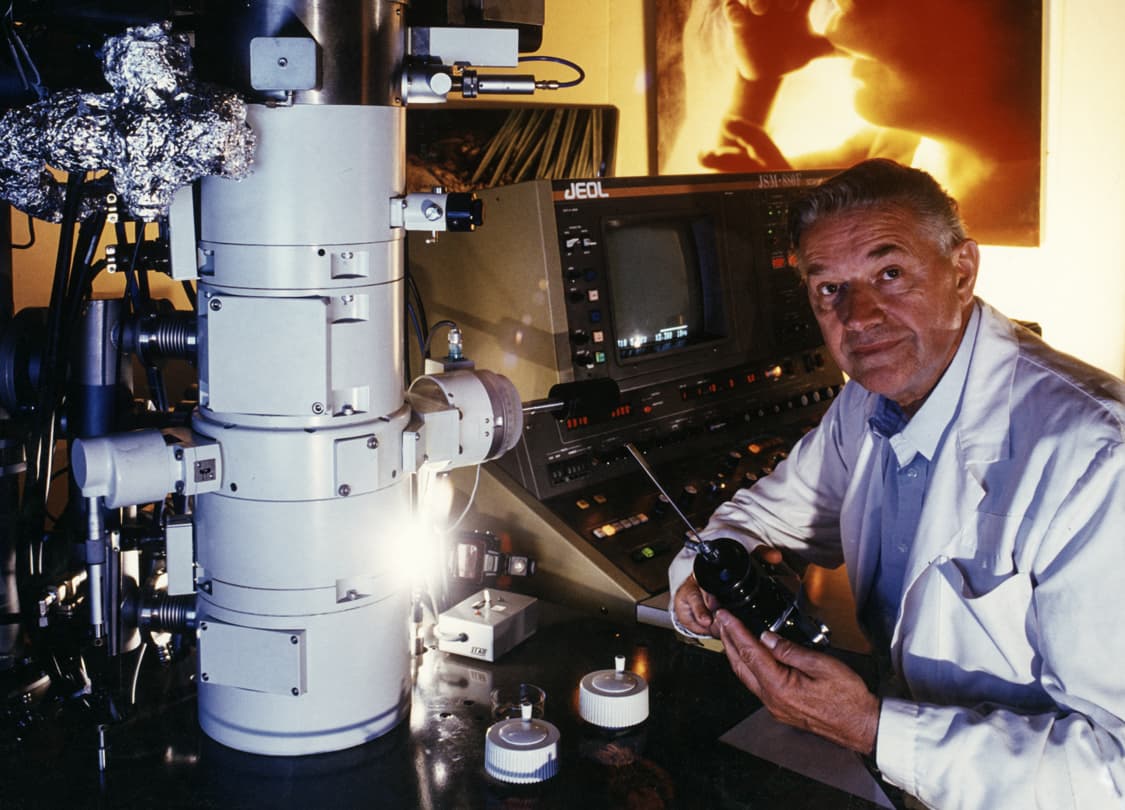

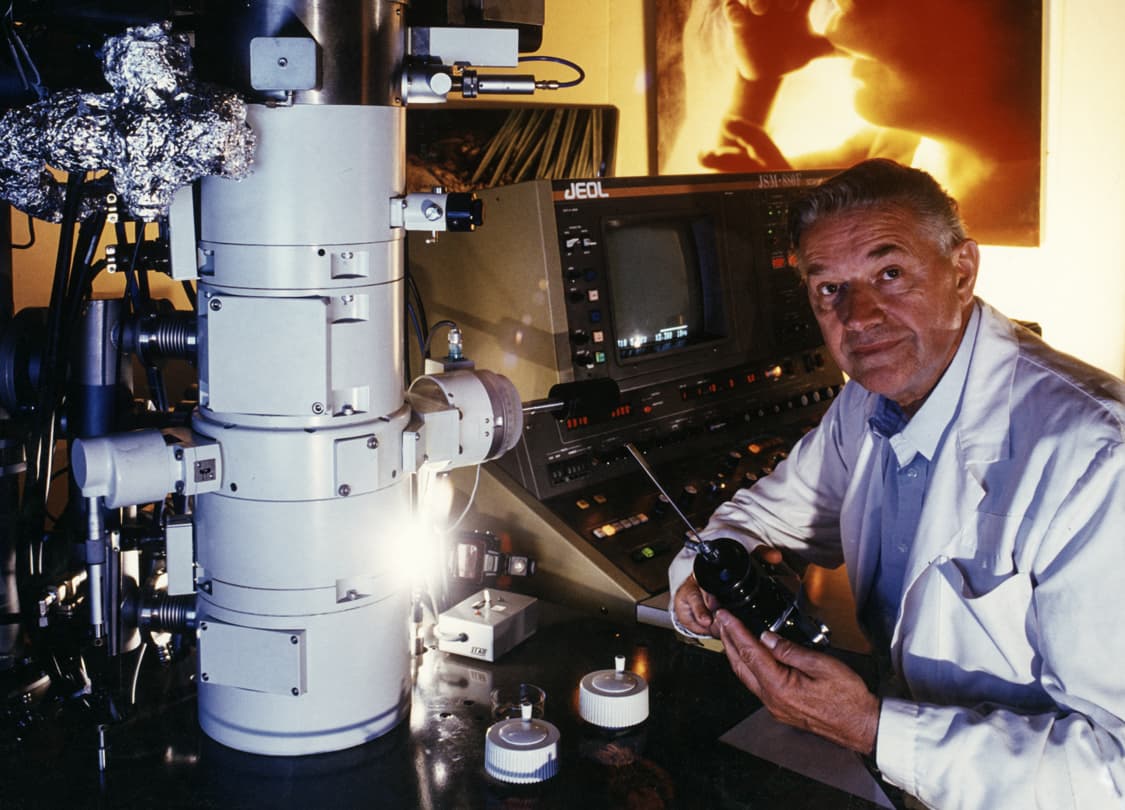

Lennart Nilsson (Figure 1) was born on 24 August 1922 in Strägnäs, Sweden, and got his first camera when he was 11 years old. Lennart’s father, an engineer, cultivated in him a flair for problem-solving and encouraged his technical acumen, and instructed him in the rudiments of photography. At the age of 12, Lennart obtained his first microscope, which he used primarily to photograph biological specimens, triggered by a documentary on Louis Pasteur [1]. His professional trajectory commenced in the domains of war and portrait photography. In the 1940s and 1950s, Nilsson published a series of photo essays in Sweden, covering a diverse range of subjects including polar bear hunting, the lives of ants and prominent Swedish cultural figures [2,3]. The artist's inaugural exhibition was held in 1955 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York [4]. In 1959, he published a highly regarded work on ants.

In 1951, a position at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm provided him with the opportunity to pursue his research interests. His investigation revealed human embryos that were only a few weeks old in a laboratory setting [2]. He expressed astonishment and fascination at the advanced stage of development of the foetuses, which had reached eight weeks of gestation at that point. Following meticulous deliberation and evaluation of all available options, he decided to focus on early human development. It appears that he had identified his life's vocation. Starting in 1953, Lennart increasingly focused on scientific photography and documentary filmmaking. When Dag Hammarskjöld was appointed UN Secretary-General in 1953, he was tasked with documenting the Swedish diplomat’s journey from the Ministry for Foreign Affairs in Stockholm to the UN building in New York [3]. When he presented the photos of Dag Hammarskjöld to the editors at Life magazine, he also took the opportunity to show them his first images of the human embryo. This moment marked the beginning of his medical career. He was widely regarded as a pioneer in the field of microscopic photography of human body tissue, bacteria and viruses (Figure 2). Subsequently, Nilsson performed intrauterine photography using endoscopes. In 1965, Lennart Nilsson's photograph of an embryo swimming in its amniotic sac was featured on the cover of the New York magazine "Life" (Figure 3) [5]. The article portrayed the developmental stages of the human embryo and foetus. It covered the stages from conception to birth. Eight million copies of Life sold out in three days, rapidly establishing the photographer’s international prominence. This paved the way for the book "A Child is Born," which was published in over 20 countries and remains a bestseller to this day [6]. A particularly notable image is that of a foetus seemingly engaged in sucking its thumb. The photographic material for the book was collected in close collaboration with distinguished scientists from Sweden and other countries, with the perfectionist Lennart Nilsson repeatedly pushing the technical limits of what was possible. Lennart Nilsson's images, particularly those depicting the foetus, served as a source of inspiration for Stanley Kubrick in creating the final scene of his 1968 movie “2001: A Space Odyssey”. The scene depicts an embryo gazing outwards at Earth from within its amniotic sac, thereby acquiring a universal perspective of new life [7].

Lennart Nilsson's images have been known to cause a degree of disruption to established patterns of discourse, notably the distinction between science and popular media. He was always demanding more from his work than he could see at first glance. He always sought to delve beneath the surface and gain a comprehensive understanding of matters. He had a particular talent for highlighting the hidden beauty of the natural world. He did this even in places where we might not have suspected that a surface even existed. His work was more than just images; they were a source of insight. In January 2017, Lennart Nilsson passed away after a lifetime of work documenting the origins of life [1]. In recognition of his contributions, the Karolinska Institute established the Lennart Nilsson Award in 1998, presented annually to individuals who have made exceptional contributions to scientific photography. I am honoured to receive this award and will present my scientific photographic oeuvre, illustrated through selected images [8].

The phrase 'form follows function' was originally coined by Louis Sullivan (1856-1924) [9]. This concept was then perfected by the German Bauhaus design group. With their principle of 'form follows function', the Bauhaus movement initiated a design revolution that continues to be influential to this day. The Bauhaus style is considered groundbreaking in modern architecture and design thanks to its clear design language, which emphasises the integration of functionality and aesthetics [10].

In anatomy, the principle of "form follows function" holds that the shape and structure of a body part are closely tied to its function. For example, the multifaceted eye of a wasp (Figure 4) is arranged into thousands of small visual units (ommatidia) to ensure a wide field of view and highly motion-sensitive vision. Similarly, the thick walls of the heart's left ventricle provide the necessary strength to pump blood throughout the body, while the broad surface of the lungs maximises gas exchange (Figure 5A) This principle underscores the notion that anatomical structures are not random; they evolve and adapt over time to best serve the functions essential to survival and efficiency, whereas in disease, this structural-functional relationship is evidently disturbed, resulting in functional loss and structural adaptation. Thereby, morphological changes caused by injury, genetic mutation or chronic stress often lead directly to functional impairment. Respiratory diseases are a prime example of this phenomenon. It is important to note that these include, in particular, chronic lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), lung cancer and pulmonary fibrosis [11] (Figure 5B-E). It is evident that the pathogenesis of these diseases may be linked to significant regenerative remodelling processes or compensatory lung growth. It can thus be concluded that the preservation of an intact alveolar vascular architecture is of critical importance for maintaining the integrity of the functional pulmonary blood-gas-barrier [12-14]. Similarly, severe COVID-19 (Figure 5B) is linked to vascular involvement, with autopsies showing alveolar capillary microthrombi nine times more common than in influenza. Also underpinning the interrelatedness of structure and function, microcirculation studies reveal distorted microvasculature, increased bronchial flow and heightened angiogenesis, while severe cases often show significant endothelial injury [15-18].

A further compelling illustration of the structure-function correlation can be observed in the development of cancer, as exemplified by the adenoma-cancer sequence in colorectal carcinomas, as delineated by Vogelstein et al. [19] in 1988 with the corresponding somatic mutations (APC, KRAS and p53). The Vogelstein hypothesis posits that cancer develops through a series of genetic mutations, while functional morphology elucidates how these alterations modify tissue structure and function, thereby transforming normal cells into tumours (Figure 6).

The human body contains a vast network of blood vessels, with an estimated total length exceeding 60,000 miles (twice as long as the equator), including at least 19 billion capillaries [11]. This means that, under physiological conditions, cells are located no further than 100–200 μm from the nearest capillary [20]. Additionally, it has been shown that blood vessels can adapt to the diverse characteristics of human tissues. Thus, it is evident that organs exhibit a high degree of variability in relation to their physiological characteristics (Figure 7). Thereby, the formation of new blood vessels, also known as angiogenesis, can be defined as the physiological process through which novel blood vessels form from pre-existing vessels. Angiogenesis is a vital process in growth, development and wound healing [21, 22]. Nevertheless, it is also a crucial stage in the shift of tumours from a harmless to a harmful state [23, 24]. It is a fundamental and dynamic biological process that occurs in both normal and malignant development. It is evident that two discrete mechanisms of angiogenesis are distinguishable: sprouting and intussusception.

Intussusceptive (nonsprouting) angiogenesis [21, 22] is a well-known process that shapes the formation of new blood vessels in cancer [24], inflammation [25, 26] and regeneration [27, 28]. Intussusceptive angiogenesis is a rapid process that results in the formation of two tubes from a single vessel. Intussusceptive angiogenesis is distinct from sprouting angiogenesis in that it does not require cell proliferation, can rapidly expand an existing capillary network and can ensure organ functionality during replication [21]. It has been demonstrated that this process facilitates the proliferation of new blood vessels in tissues where they are absent. The interconnection between branch-angle remodelling and intussusceptive angiogenesis is exemplified by the intussusceptive pillar. It appears that this process is governed by minute forces present within the blood and the pressure exerted on the vessel walls [25, 26]. This pillar formation and branch remodelling may represent an important adaptive mechanism in the body, allowing it to cope with elevated blood flow and pressure during periods of inflammation and regeneration. The intussusceptive angiogenesis process is initiated within minutes. The presence of pillars is evident after a period of 15 to 30 minutes.

The microvascular corrosion casting technique has been utilised for nearly five decades to create replicas of both normal and abnormal vasculature and microvascular architecture in various tissues and organs [20]. Combined with scanning electron microscopy (SEM), microvascular corrosion casting has the capacity to elucidate, delineate and enumerate the morphological characteristics and anatomical distribution of blood vessels in these tissues. The architectural design of vessel systems can be analysed using two- or three-dimensional models. It has a high depth of focus and a reasonably high resolution, facilitating the visualisation of the microvascular bed. In addition, it enables reliable differentiation between arteries and veins by characteristic endothelial cell imprints [20]. Microvascular corrosion casting is used to image disease-related changes in vascular structure. Alzheimer's disease is a prime example of these neurovascular changes, which have a significant impact on brain function due to alterations of the neurovascular unit comprised of neurons, glia and vascular cells [29, 30]. These changes can result in neuronal injury due to impaired cerebral perfusion, unregulated entry of circulatory compounds into the brain, reduced cerebral amyloid clearance and the accumulation of vascular and parenchymal elements. The vascular system in Alzheimer's disease [30, 31] exhibits typical vascular changes such as pompon-like microaneurysms (Figure 8).

Synchrotron radiation is the most intense type of X-ray radiation available. It has seen significant development in recent decades. Synchrotron radiation was initially described in 1947. Subsequently, interest in synchrotron radiation has grown, especially in physics and solid-state research. In recent decades, new opportunities have arisen in research and diagnostics. Synchrotron radiation is based on the movement of electrons [32, 33]. When electrons move at a sufficiently high velocity, they emit energy exceeding that of X-ray waves. The electrons are fed into the booster synchrotron and accelerated to a high speed. This raises them up to 6 gigaelectronvolts (GeV). Importantly, changes in the beam result in a loss of energy. This energy can then be used as synchrotron radiation to produce images. The use of special magnets is essential for ensuring that the radiation is coherent and bright. This technology is comparable to modern laser radiation. Synchrotron radiation is a hundred billion times brighter than a conventional X-ray source used in medical imaging. This enhancement in visibility is a considerable advantage over conventional computed tomography methods. Most conventional imaging techniques used in clinical practice exploit the attenuation of X-rays as they pass through tissue [34]. The hierarchical phase-contrast tomography technique also uses attenuation effects. The phase shifts of electromagnetic radiation are converted into intensity fluctuations. These are recorded by the detector and reconstructed in three dimensions with high edge sharpness.

In 2020, the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) in Grenoble (Figure 9), France, was upgraded to a "fourth generation" X-ray source. Subsequently, we have developed a technique known as hierarchical phase-contrast tomography (HiP-CT) [35, 36]. This is a synchrotron X-ray tomography technique that creates hierarchical image volumes of ex vivo intact human organs, spanning the scales from the single cell to the whole organ (HiP-CT). This multiscale capability makes hierarchical phase contrast tomography particularly valuable in fields like biology, materials science and medicine, where both structural context and fine microarchitecture are crucial for interpretation [37, 38]. In recent years, we have launched the Human Organ Atlas Hub (HOAHub), an international initiative based at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) that uses hierarchical phase-contrast tomography (HiP-CT) to create a high-resolution, open-access 3D atlas of whole human organs at cellular resolution. This project aims to bridge imaging scales from clinical scans to molecular resolution, build a public atlas of organs in health and disease and advance biomedical research by providing detailed datasets for scientists and medics worldwide. To illustrate, we provide an image of a human placenta (Figure 10). Additionally, we are conducting the world's only clinical studies that use HiP-CT for multimodal and multiscale comparisons in the diagnostics of breast cancer (Figure 11), lung cancer and prostate cancer [38]. Our Himalaya project (HIMALAYA: Holistic Imaging and Molecular Analysis in Life-Threatening Ailments, www.himalaya-project.net) aims to improve the diagnosis and risk assessment of prostate cancer. To this end, new experimental imaging techniques are being employed that provide unparalleled resolution of prostate cancer. The high image quality, in conjunction with histological examination and further molecular tests, helps us interpret magnetic resonance images more accurately. This will enable us to develop a stronger understanding of prostate cancer and devise new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in the near future.

Correspondence Maximilian Ackermann. E-mail: maximilian.ackermann@uni-mainz.de

Accepted 5 December 2025

Published 20 January 2026

Conflicts of interest none. The author has submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. It is available together with the article at ugeskriftet.dk/dmj

Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to Anne Fjellström (Lennart Nilsson Photography AB) for her invaluable support and for the use of Lennart Nilsson's images. I acknowledge the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) for the provision of synchrotron radiation facilities under proposal numbers MD-1252, MD-1290 and MD-1389, and Siemens Healthineers, especially Klaus Engel, for providing the cinematic rendering software

Cite this as Dan Med J 2026;73(2):A10250883

doi 10.61409/A10250883

Open Access under Creative Commons License CC BY-NC-ND 4.0